Patrick Procktor

British, born Ireland

British, born Ireland, (1936–2003)

Patrick Procktor, who has died aged 67, had his first show at the Redfern gallery in Cork Street, London, within a year of setting out his stall as a professional artist. It was 1963, the year of Beatlemania; the year David Hockney began his own progress from student rags to jet-setting riches with the sale of the complete edition of his Rake's Progress suite of etchings. It was the decade in which working-class artists, footballers and pop stars first said "up yours" to establishment values, and young painters began to bask in something like pop star celebrity and footballers' salaries, selling to royalty, being interviewed for colour magazines and photographed by Snowdon.

Procktor's show was a sell-out before the opening. A year later Bryan Robertson selected him for the first and most famous of the New Generation exhibitions at the Whitechapel gallery, the show that helped propel co-exhibitors like Hockney, Bridget Riley and John Hoyland into their careers.

As it happened, Procktor's celebrity did not keep pace with Hockney's, but as his reputation diminished, his prolific output of painting and graphic work became finer, marked by an exquisite sense of colour and design.

He himself was too tall - well over 6ft - to be an exquisite, but flamboyant he certainly was. He dressed exotically and, like Hockney, flaunted his homosexual preferences; unlike Hockney, this was to the detriment of his sales from at least one exhibition, in 1968 in New York, which he devoted to paintings of his lover at the time, Gervase Griffiths. It was a one-man show which Procktor insisted on calling a one-boy show. Its failure, though, was probably more a comment on an uncharacteristic lack of variety than an expression of homophobia.

Procktor was born in Dublin, the younger son of an oil company accountant, but when his father died in 1940 the family moved to London. Patrick went to Highgate school from the age of 10 and, though he enjoyed the art lessons given by the landscape painter Kyffin Williams, he wanted to read classics at university. His hopes were dashed because his mother's wages as a hotel housekeeper were sufficient only to sustain the older brother in further education. Patrick left school early to work at a builders' merchants and joined the Royal Navy at 18: there his talent for languages earned him the most popular and useful of cushy national service options, a training in Russian.

After demob he held down a day job as a Russian interpreter with the British Council, on whose behalf he made many journeys to the Soviet Union; the evenings he devoted to painting and drawing, and on the basis of a single picture hung in a mixed summer exhibition at the Redfern, he was accepted in 1958 as a student at the Slade School, where the formidably influential William Coldstream was professor of fine art. Fortunately for Procktor's maverick talents, he befriended Keith Vaughan and later met Hockney, then a student at the Royal College of Art.

Though Procktor worked with oils and acrylics, he also used watercolour extensively, and very largely the techniques he learned for this deeply unfashionable medium measured the distance between his work and that of his contemporaries.

British pop art came in two strains: one, fostered by the older generation of Richard Hamilton, Eduardo Paolozzi, Nigel Henderson, and the architects Peter and Alison Smithson, was cerebral and self-consciously socially aware; the other, in which Hockney, David Oxtoby, Allen Jones and Patrick Caulfield were the stars, was more instinctively drawn to the ambient visual imagery of popular culture expressed in anything from graffiti to advertising. Procktor's work lay on the verge of the second group; not pop, but drawing on pop's preference for non-realistic colour and flatness of surface in an edgy and wittily articulated figurative formulation.

He travelled widely, and some of the work he did in Bombay and Venice in the early 1970s suggested a sensibility open to the refined and economical sense of space in the art of the far east that he was to adapt to his own work after visits to China and Japan - the delicate handling of one highly successful portrait of Jimi Hendrix even succeeds in making the guitarist look like a 20th-century samurai.

Procktor travelled light, carrying his box of watercolours and using the results of his work abroad as the basis for richly rewarding series of graphics. He had a long collaboration with the brilliant printmakers Alecto, and throughout his life stayed with the Redfern gallery, though he notched up exhibitions with other galleries all over the world. One of the best of his sets of prints was a sequence for a new edition of The Rime Of The Ancient Mariner, based on Gustave Doré's famous engravings but with a sense of the light fantastic very distant from Doré's gloomily gothick imaginings. On the basis of his first sell-out exhibition, Procktor bought and furnished the flat in Manchester Street, Marylebone, which he kept all his life, close to the great gathering of 18th-century rococo artists in the Wallace collection to whom, it became evident as he matured, he was close in feeling if not in method or intention.

He was elected Royal Academician in 1996, and though he turned out to be an obstreperous member of this organisation, he remained a social success in a wider sphere. Long before he studied art he had made friends in artistic circles, starting with Richard Buckle, the organiser of the great Diaghilev exhibition in London in 1954, from whom Procktor acquired a lifelong love for theatre in general and Russian ballet in particular. This was reflected in his painting just as his acquaintance with pop stars brought him commissions for record sleeves.

Apart from Vaughan, Buckle and Hockney, his social circle included Derek Jarman, Francis Bacon and Cecil Beaton, a gay grouping some at least of whom must have raised their eyebrows when, in 1973, he married Kirsten Benson: she and her husband James Benson had been neighbours of Procktor in Manchester Street and were the founders of Odin's restaurant. The three became friends and travelling companions.

After James was killed in a traffic accident, Procktor married Kirsten. She sold the restaurant to Peter Langan, and Procktor and other artists he introduced to Langan, from Hockney to Bacon and Lucian Freud, gave paintings to hang on the walls of Odin's as well as Langan's Brasserie in return for hospitality - a wonderful embellishment for the establishments and a pretty good bargain for Langan.

Kirsten died in 1984, but their son survives Procktor.

British, born Ireland

British, born Ireland, (1936–2003)

Patrick Procktor, who has died aged 67, had his first show at the Redfern gallery in Cork Street, London, within a year of setting out his stall as a professional artist. It was 1963, the year of Beatlemania; the year David Hockney began his own progress from student rags to jet-setting riches with the sale of the complete edition of his Rake's Progress suite of etchings. It was the decade in which working-class artists, footballers and pop stars first said "up yours" to establishment values, and young painters began to bask in something like pop star celebrity and footballers' salaries, selling to royalty, being interviewed for colour magazines and photographed by Snowdon.

Procktor's show was a sell-out before the opening. A year later Bryan Robertson selected him for the first and most famous of the New Generation exhibitions at the Whitechapel gallery, the show that helped propel co-exhibitors like Hockney, Bridget Riley and John Hoyland into their careers.

As it happened, Procktor's celebrity did not keep pace with Hockney's, but as his reputation diminished, his prolific output of painting and graphic work became finer, marked by an exquisite sense of colour and design.

He himself was too tall - well over 6ft - to be an exquisite, but flamboyant he certainly was. He dressed exotically and, like Hockney, flaunted his homosexual preferences; unlike Hockney, this was to the detriment of his sales from at least one exhibition, in 1968 in New York, which he devoted to paintings of his lover at the time, Gervase Griffiths. It was a one-man show which Procktor insisted on calling a one-boy show. Its failure, though, was probably more a comment on an uncharacteristic lack of variety than an expression of homophobia.

Procktor was born in Dublin, the younger son of an oil company accountant, but when his father died in 1940 the family moved to London. Patrick went to Highgate school from the age of 10 and, though he enjoyed the art lessons given by the landscape painter Kyffin Williams, he wanted to read classics at university. His hopes were dashed because his mother's wages as a hotel housekeeper were sufficient only to sustain the older brother in further education. Patrick left school early to work at a builders' merchants and joined the Royal Navy at 18: there his talent for languages earned him the most popular and useful of cushy national service options, a training in Russian.

After demob he held down a day job as a Russian interpreter with the British Council, on whose behalf he made many journeys to the Soviet Union; the evenings he devoted to painting and drawing, and on the basis of a single picture hung in a mixed summer exhibition at the Redfern, he was accepted in 1958 as a student at the Slade School, where the formidably influential William Coldstream was professor of fine art. Fortunately for Procktor's maverick talents, he befriended Keith Vaughan and later met Hockney, then a student at the Royal College of Art.

Though Procktor worked with oils and acrylics, he also used watercolour extensively, and very largely the techniques he learned for this deeply unfashionable medium measured the distance between his work and that of his contemporaries.

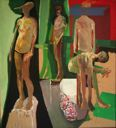

British pop art came in two strains: one, fostered by the older generation of Richard Hamilton, Eduardo Paolozzi, Nigel Henderson, and the architects Peter and Alison Smithson, was cerebral and self-consciously socially aware; the other, in which Hockney, David Oxtoby, Allen Jones and Patrick Caulfield were the stars, was more instinctively drawn to the ambient visual imagery of popular culture expressed in anything from graffiti to advertising. Procktor's work lay on the verge of the second group; not pop, but drawing on pop's preference for non-realistic colour and flatness of surface in an edgy and wittily articulated figurative formulation.

He travelled widely, and some of the work he did in Bombay and Venice in the early 1970s suggested a sensibility open to the refined and economical sense of space in the art of the far east that he was to adapt to his own work after visits to China and Japan - the delicate handling of one highly successful portrait of Jimi Hendrix even succeeds in making the guitarist look like a 20th-century samurai.

Procktor travelled light, carrying his box of watercolours and using the results of his work abroad as the basis for richly rewarding series of graphics. He had a long collaboration with the brilliant printmakers Alecto, and throughout his life stayed with the Redfern gallery, though he notched up exhibitions with other galleries all over the world. One of the best of his sets of prints was a sequence for a new edition of The Rime Of The Ancient Mariner, based on Gustave Doré's famous engravings but with a sense of the light fantastic very distant from Doré's gloomily gothick imaginings. On the basis of his first sell-out exhibition, Procktor bought and furnished the flat in Manchester Street, Marylebone, which he kept all his life, close to the great gathering of 18th-century rococo artists in the Wallace collection to whom, it became evident as he matured, he was close in feeling if not in method or intention.

He was elected Royal Academician in 1996, and though he turned out to be an obstreperous member of this organisation, he remained a social success in a wider sphere. Long before he studied art he had made friends in artistic circles, starting with Richard Buckle, the organiser of the great Diaghilev exhibition in London in 1954, from whom Procktor acquired a lifelong love for theatre in general and Russian ballet in particular. This was reflected in his painting just as his acquaintance with pop stars brought him commissions for record sleeves.

Apart from Vaughan, Buckle and Hockney, his social circle included Derek Jarman, Francis Bacon and Cecil Beaton, a gay grouping some at least of whom must have raised their eyebrows when, in 1973, he married Kirsten Benson: she and her husband James Benson had been neighbours of Procktor in Manchester Street and were the founders of Odin's restaurant. The three became friends and travelling companions.

After James was killed in a traffic accident, Procktor married Kirsten. She sold the restaurant to Peter Langan, and Procktor and other artists he introduced to Langan, from Hockney to Bacon and Lucian Freud, gave paintings to hang on the walls of Odin's as well as Langan's Brasserie in return for hospitality - a wonderful embellishment for the establishments and a pretty good bargain for Langan.

Kirsten died in 1984, but their son survives Procktor.

Artist Objects

Lido in Venice 2006.042

Parade 2004.003